Atsushi Hirano Semisolid Work 「a measure of beauty」 #009

Atsushi Hirano Semisolid Work 「a measure of beauty」 #009

2024-08-19

©︎Atsushi Hirano

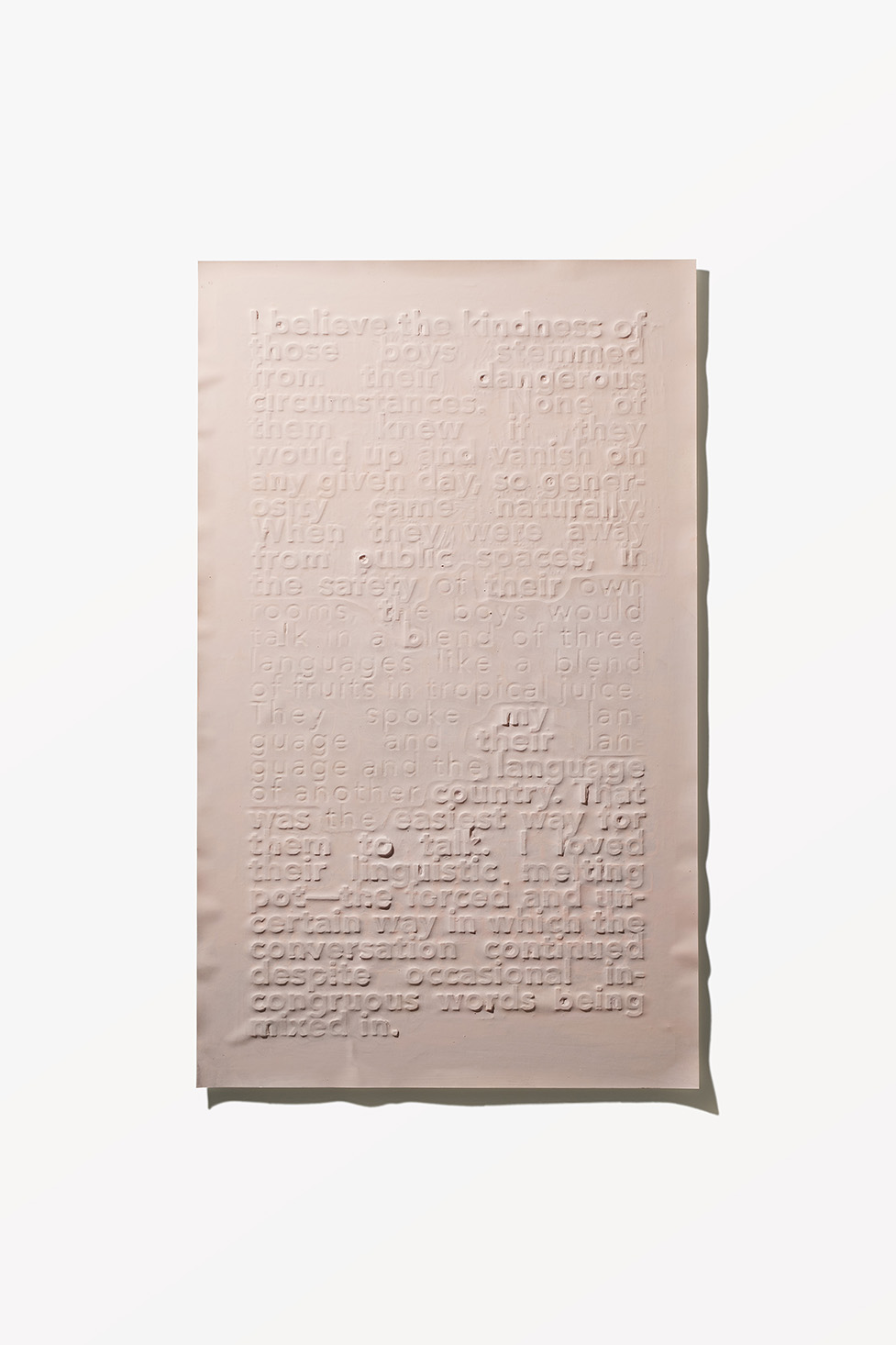

Title: a measure of beauty #009[pink]

Size:430mm×525mm

Material: Paper

Method: Hand carved & Hand print

Text: Miho Kaneda

Year of production: 2019

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

以下 作品テキスト

1つの作品には、以下のテキストの意味を分解する形で、16種類に分かれており、

それは、心象風景としての意味を持ちます。

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

美しさの尺度

学校の近くに、ある宗教を信じている人が住んでいるって噂の場所があったの。それまでも彼らはひっそりと暮らしていたけれど、とある事件を境に、地元の住民が彼らをそこから追い出そうとした。私は出て行ってほしいともそこにいてほしいとも思わなかったけれど、友達の女の子は「みんなが出て行けって言ったら、あの人たちはどこに行くんだろうね」と私に向かって吐き出すように言ったの。私はそれを確かに聞いた。小学校6年生の春だった。彼らは不思議な言葉を話していた。あまり聞いたことのない、遠い国の言語だった。外に出るときは黒いヴェールで顔を隠して、心の奥深くに踏み込まれないように、シャッターを下ろしているみたいだった。ときどきブルーの液体が身体の外に流れ出てきていた。彼らは海を渡って遠くから来たようだった。「Hello!」と声をかけたら困った顔をしたから、今度は「こんにちは」って言ったら「こんにちは」って返してきた。どっちも自分の言葉じゃない。けど今どっちを使うのがふさわしいか、良く知っているみたいだった。見えない敵はすぐ近くにいるわ。素性を明かすのは危険よ。ある時、女の子は彼らに「ブルーの液体が流れてるよ」ってそっと忠告をした。彼らは一斉に早口で何かの話をし始めたの。それから泣いた。友達は黙って聞いていた。私は遠くでその姿を見ていたわ。そして彼らは話し終わると友達にハグをして、建物の中に消えていったの。それが彼らを見た最後の日だった。彼らはそれ以来、どこかへ消えてしまった。友達は次の日も前と同じように学校に来ていた。胸に綺麗な色のブローチが付いていたこと以外、以前と何も変わらなかった。彼らを消したのは私だったかもしれないわ。あるいは彼女。あるいは他の誰か。

中華料理店のテーブルは丸くて、料理を載せた台がくるくると回るの。こちらの料理に手を伸ばそうとすると、あちらの料理が回る。「あ!」って顔した向かいの男の子と目が合う。そんな風に世界がつながってるのが好きだった。食事を囲む8人全員が円の一部分を構成していて、私が席につくと両方の目に7人の顔が同時に映るでしょう。その光景を私は気に入っていたの。円卓は終わりのない遠近法だった。

私はある国で3人の男の子に出会ったわ。彼らはどこの生まれだとか所属だとか、そういうものに一切興味がないようだった。ある一定期間に人格を形成する一部になったという以上の興味はね。そのことは私を安堵させたの。そして彼らは自分の居場所を探しているようだった。皆が故郷に帰る時「僕らには帰る場所がないからね」と冗談めかして話していたのを私は聞いていたの。彼らには彼らのルールがあった。決してマジョリティになることのないその国で、自分たちなりのルールを作って暮らしていた。一人が困ったら皆でお金を出し合い、家がなければ誰かの部屋にしばらく泊めてやり、そうしてお互いに助け合っていたように見えた。彼らは3つの言葉を自在に操った。だけど、誰一人としてそのことを公にしようとはしなかったの。ただ意思疎通のために、的確に3つを操っていた。そうしているうちに、彼らは自分が何者なのか分からなくなっていった。私にはそんな風に見えた。彼らはそろって優しかったけど、それは悲しいからだった。いつも破滅しそうなぎりぎりだったし、突然誰かが姿を消すこともあった。でも、誰も何も言わなかった。しばらくしたら戻ってくるだろうって、もう慣れているみたいだった。彼らは外では決して彼ら自身の言語で話さなかった。特に地下鉄の中ではそうだった。でもそれは嫌っているからじゃなく、むしろ彼ら自身が彼らの言語を誇りに思っていたからだったわ。彼らは薄っぺらなコミュニケーションのために言語が消費されることを恐れた。異国の地で自分達の言語がそんな風に消えていくことは、望ましくないことだと考えていた。一時的に流行して、広まって、そして時代に流されて消えていくことを恐れた。私はそのことについて彼らに聞いたことがあったの。「お前には自分の言葉を堂々と話せない屈辱が分かるか」と言った。「わからないわ。」彼らは彼らなりの方法で自分達の言語を守った。決して外に漏らさぬようにしていたし、磨り減らさぬように大事にしまっていたの。そうすることがやがて忘れ去られ古くなり、誰もそれを使わなくなることとイコールだとも知らずに。あるいは知っていたのかもしれないけど、それが3人で決めた約束なのかもしれなかった。それは今となってはどちらでもいいことなの。私が彼らと別れて何年かして、彼らのうちのひとりが地下鉄に轢かれて消えた。「地下鉄に轢かれて消えた。」私はインターネットのニュースでそのことを知った。11文字のニュース。私は何度も忠告したはずだった。「地下鉄のドアに挟まってはいけないわ。」忠告、17文字の。だけれど日常は続いていた。その国は雲隠れできる場所だったし、誰も干渉しない場所だった。そして儚い場所だった。彼らの優しさは危うさから来ているのだと思った。いつ消えるか誰にもわからない、だから寛容になれるのだった。公ではない場所で、つまり誰かの部屋の中で、彼らは3つの言語をミックスジュースみたいに混ぜて話したの。つまり、私の言語と彼らの言語とある国の言語の3種類。それが一番話しやすいようだった。私は彼らの言葉のチャンポンが好きだった。会話の中に時折異質な単語が混ざって、それでも意味が繋がっていく強引で不確かなところ。1つの言語を解体してそれをもう一度組み立て直して、中途半端で未完成な何かを使って伝えようとする姿勢がたまらなく可笑しかった。3つの言語が重なって、何物でもない言葉が生まれる時間が心地よかった。それはこの世界の優劣をすべて取っ払ったような、フラットな世界に感じられたわ。人が形あるものにとらわれずに、ただ伝えようとすることは、原始的なコミュニケーションのあり方のように思えた。何より3つが混ざったその音は私の心に響いたの。だけど一歩外へ出ると彼らは沈黙したわ。彼らは自分達の信念を守った。だから彼らを理解する者はいなかった。私は彼らに、私の知らない母国のことを教わった。日本の東京のことだった。国からもらった奨学金は3日で使い果たせること、歌舞伎町の公衆電話は別の世界に繋がっていること、デパートのアルバイトでもらった高級な刺身は川に流すべきだってこと。彼らの目には私の知らない私の国が見えていた。それは理解できないことだらけだった。割り切れないもの、境界にあるもの、道端のポケットにストンと落ちてしまうもの。彼らが3つの言語の間を行き来しながら見ていたものは何だったの。誰にも拾われない社会の澱みたいな部分を掬い上げながら、それでも飄々と生き抜く彼らは不器用で間抜けで格好悪かった。

「みんなが出て行けって言ったら、あの人たちはどこに行くんだろうね。」出て行くってどこから?どこへ行けというの?根無し草には根無し草なりの言い分があって、それは大抵この世界の均衡とは無関係なところで動いていた。けれど時折無防備に現れてこの世界に影響を与えるのだった。不確かで儚く脆いもの。緩やかで流動的で危ういもの。相反する2つの感情を携えて右に左に揺れながらそれでも前に進むもの。彼らが最後に辿り着くユートピアみたいな場所がこの世の何処かにあるのなら、いつか行ってみたいと思った。世界はギリギリの均衡で回ってる。多くの不可思議な出来事とともに。だから混沌は混沌のまま受け入れなきゃいけないの。そうじゃないと、この世の中には理解できないことが多すぎる。だけど一つ言えることは、大きな荷物を抱えながら自分の足で立っている人達を、私はきちんと見ていなきゃってことなの。美しさって案外それだけのことかもしれないのよ。

A measure of beauty

It was rumored that the people who lived near my school were followers of a certain religion. For a while, they lived there quietly without drawing any attention, but then something happened to make the other locals try to drive them out. I didn’t mind whether these people stayed or left, but a girl I was friends with said, “If everyone tells them to leave, where are they supposed to go?” I heard what she was saying. It was spring, and we were in sixth grade. The people who were the topic of the rumors spoke a strange language from a distant country, one we’d rarely heard before. They hid their faces with black veils when they went outside, as if putting up barriers so that no one could step too deeply into their hearts. Sometimes, blue liquid seeped out of their bodies; they seemed to have journeyed here from a faraway place across the ocean. When we greeted them with “hello,” they gave us a puzzled look, so we tried “konnichiwa,” and they returned the greeting. Neither language was theirs, but they seemed to know which one was more appropriate. Our enemy is hiding close by; to reveal our true selves is dangerous! One day, my friend told them discreetly, “You’re leaking blue liquid.” They suddenly started talking over each other in rapid voices before bursting into tears. My friend listened to them in silence. I watched from afar. When they finished talking, they hugged my friend and withdrew into their homes. That was the last day anyone saw them. My friend came to school the next day as usual. Aside from a beautifully colored brooch that she wore at her chest, nothing had changed. Maybe I was the one who made them disappear. Maybe it was her. Or maybe it was someone else.

The table in the Chinese restaurant was circular with a food stand that rotated round and round. When I reached for a dish on my side of the table, the dish on the other side spun too. The boy sitting across from me made a surprised face, and our eyes met. I loved how our worlds were connected like that. Each of the eight people around the table formed one part of a circle. When I sat down, the faces of the other seven were equally reflected in my eyes. There was something pleasing to me about that scene. The circular table allowed for a complete and endless perspective.

I met three boys in another country. None of them viewed matters like where they were born or where they worked with any importance. These experiences only mattered because, for a short while, they had helped to shape their characters. This put me at ease. The boys appeared to be searching for their place in the world. When others traveled back to their hometowns, they joked about having nowhere to return to. In a country where they would never fit in with the majority, they made and lived by their own rules. If one of them was tight for money, the others would pitch in. If one of them didn't have a place to stay, the others would offer their rooms. They helped each other out. Though they were fluent in three languages, they never revealed this to other people. They wielded these three languages with great precision to communicate with each other. As a result, the boys gradually lost track of who they were. They were warm and kind, but that was because they were also sad. The group always teetered on the verge of coming undone, and one of them would sometimes vanish unexpectedly. Yet nobody said anything. It seemed as though they were used to this state of affairs, like it was nothing special, and the lost boy would come back soon enough. They never spoke their own language in public—especially not on the subway. This wasn’t out of hatred for their language; it was because they were proud of it. They feared the language would be expended in trivial conversation and fade out of existence in that foreign land. They feared the language would spread and become popular for a time before being buried with the passing of the ages. I questioned them about this once. One of them responded, "Do you understand how humiliating it is not being able to speak your own language out in the open?" I did not. They were protecting their language in their own way, carefully guarding it from the outside world so that it would never be diminished. Little did they know that doing so meant the language would eventually grow old and be forgotten, spoken by no one. Or maybe they did know, but that was how they had promised each other to handle their language. But all of this matters little now. Many years had passed after I parted ways with the boys when one of them was hit by a subway and disappeared forever. “Hit by a subway and disappeared forever.” I learned this from an article I read online. A short, seven-word news. How many times did I warn him? “Don’t get caught between the doors on the subway,” I said—a nine-word warning. Nevertheless, life went on. It was easy to disappear in that country, where no one ever interferes. Life in this place was fleeting, short-lived. I believe the kindness of those boys stemmed from their dangerous circumstances. None of them knew if they would up and vanish on any given day, so generosity came naturally. When they were away from public spaces, in the safety of their own rooms, the boys would talk in a blend of three languages like a blend of fruits in tropical juice. They spoke my language and their language and the language of another country. That was the easiest way for them to talk. I loved their linguistic melting pot—the forced and uncertain way in which the conversation continued despite occasional incongruous words being mixed in. I found it irresistibly funny to watch them dismantle a language and build it up again using half-baked, unfinished concepts to try to convey their thoughts. The time they spent creating words that belonged to no one and no place, from the overlap of three different languages, was truly pleasant for me. It felt as if we were in a flat place where the hierarchy of the world had been discarded. It reminded me that the act of simply conveying one’s thoughts without fixating on tangible things is a primeval form of communication, and I was touched by the sound of those three languages mingled together. Yet as soon as we stepped outside, the boys fell silent as they believed was right. That’s why nobody else understood them. These boys taught me many things about my own country and about Tokyo. I learned that it was possible to spend the entirety of a national scholarship in three days, that the public telephones in the Kabukicho district connected you to another world, and that the expensive sashimi received during a part-time job at the department store should be thrown into the river. Their eyes saw things about my country that I could neither see nor understand: things that are illogical, peripheral and end up falling by the wayside. What did they see as they journeyed back and forth between three languages? These boys were scooping up the dregs of society that no one else was picking up, but they carried on with nonchalance. They were clumsy, foolish, and decidedly uncool.

“If everyone tells them to leave, where are they supposed to go?” Where is it they should leave from? Where do you expect them to go? Rootless wanderers have grievances of their own and operate in a space largely unrelated to the overall equilibrium of the world. Sometimes, they emerge without warning to exert an influence on wider affairs. They are uncertain, fleeting and fragile. They are gentle, fluid and endangered. They sway between two conflicting emotions but eventually move forward. If, at the end of their journey, they find a utopia somewhere in this world, I want to go there someday. The Earth spins on a fragile equilibrium, taking countless wonders into its orbit. We must embrace the existence of confusion and chaos; otherwise, the unfathomable things in this world threaten to overwhelm us. The one thing I can say with conviction is that I need to acknowledge the people who stand on their own in defiance of the burdens they carry. Beauty, after all, could be just that.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------